Unlearning Race

A Letter Exchange with Thomas Chatterton Williams

The correspondence below was first published on the website Letter Wiki (now defunct). Although originally written in 2019, just after the publication of Thomas’ book A Self-Portrait in Black and White, the subjects tackled here are timeless. To follow my Substack, use the button below. You can find Thomas’ Substack here. Thanks to Thomas and to Clyde Rathbone for permission to reprint these letters here.

Buenos Aires, 26 October, 2019

Dear Thomas,

I've been wrestling with this letter in my mind for a while. Your book, A Self-Portrait in Black and White: Unlearning Race knocked me for six and I'm still reeling. So I'll do what Charles Dickens describes in a missive he wrote in 1844: “plunge headlong with a terrible splash into this letter, on the chance of turning up somewhere.”

In Lies, Secrets and Silence, Adrienne Rich describes truth as a tapestry, which, when we look closely, reveals “tiny multiple threads unseen in the overall pattern.” Rich’s image seems fitting for this conversation about race, because the contrast between pattern and individual stitches parallels the mismatch between the crude, simplistic, fuzzy racial categories that we use to classify people and the rich, tangled complexity of each individual’s ancestry. All too often, we act as though we are looking at people from a mid-range distance: not far enough out for real perspective—not astronauts contemplating a green and blue marble, not a humanity-wide view—but also not close enough to recognise each individual as her own, unique microcosm. From this mid-range, we approximate, we divide, we lump.

Perhaps a good initial thread to tug to begin to unravel this is the way in which skin colour is used as a marker of authenticity. We not only divide people up into ethnic tribes, but, as I've written elsewhere, the borders are policed and, to prove your citizenship, you must display your complexion, hair texture and mien like a passport, as if we were pedigree dogs, measuring each other's ears to check that we fit the breed standard. There can be no more absurd example of this than the way you describe picking out photos of your pale-skinned, blonde, blue-eyed infant daughter:

In the pictures I took of my daughter, I found myself applying filters that made her skin tone tanner. I erased shots that looked too washed out, overexposed. Out of many, I found one in which she appeared virtually ecru, and this I forwarded to friends.

I can relate. I've done this with my own photos. Our situations are complementary: you're the brown-skinned father of a paler daughter; I'm the pale daughter of a walnut-brown father. Here's a blurry old snap of my parents, in Karachi, circa 1968. (My father is the shorter man.)

I’ve picked out the snaps of myself in which bright light obscures my freckles and my hair looks an especially glossy black. People have often doubted my parentage and I’ve become defensive about it. And, as I sit here, writing this, I'm wearing one of the kurta and churidar outfits I sport almost daily—my attempt to look and feel more Indian. But sometimes it feels like a costume. What does it mean to be Indian, to be Parsi? There is surely no secret racial essence there, somehow determining my personality, colouring my soul. The only thing really connecting me to that little band of Zoroastrians who landed on the Gujarat coast from Persia and petitioned an Indian king for asylum in the eighth century—if that apocryphal tale even has any basis in reality—is my desire to feel connected to them, my imagination. People laughed at Rachel Dolezal for pretending to be black. But, in a sense, aren’t we all pretending? Isn’t the whole notion of a racial identity a masquerade?

When we spoke on my podcast, you described feeling what I think of as a kind of survivor’s guilt. You said, “living a life that is free of suffering when you come from a historically oppressed group can feel something like treason.” You didn't want to betray the memory of those of your ancestors who came to America as slaves, but at the same time, you don’t want your daughter to be burdened with past traumas and you don’t want to “fetishise the wound” of the past, as you put it. At that time, you said that you were still struggling with those questions.

Towards the end of your new book, you describe a daydream, in which you see your daughter, in her twenties, in some European café, tell a group of surprised friends that some of her ancestors were black Americans. But it's just a casual, passing remark and they quickly move on to other subjects. You write that you feel a frisson of horror at this:

I see a history, a struggle, a culture, the whole vibrant and populated world of my ancestors—and of myself—dissolve into the void.

You are uncomfortable with the idea of “unearned advantage”—perhaps this is a concept close to what people call privilege—what does it mean, you ask, to have escaped discrimination, oppression, prejudice, suffering, just because of an accident of genetics that has given you a different skin tint? And yet I know you would not want your daughter to suffer and, as you write, people are “distinct and irreplaceable,” not mere “avatars, sites of racial characteristics and traits, reincarnations of conflicts and prejudices past.”

Have you had more thoughts about how to reconcile these conflicted feelings, these profound ambivalences? If your daughter grew up to feel that, while her immediate family was important, she had no interest in her more general ancestry, that racial categories were as quaint and outdated as star signs and of no relevance to her—what would be gained? And what would be lost? Do we owe a debt to our ancestors to feel part of that lineage or should we leave those identities behind and focus on our membership of the human race? I'm curious to hear your musings on this.

Yours with warmest love,

Iona xoxoxo

Dear Iona,

I want to open up here by noting how strong, how formidable your letter game is. You set a high bar, and I like it. And I’m touched and inspired that you found themes and ideas in my book to expand on and reinterpret through the lens of your own experience. One of the most frustrating criticisms I’ve received thus far—the book is only a week old, but some of the pushback started weeks ago—is that what I’ve written is somehow an attack on blackness. I’m grateful to you for seeing right away that it is nothing like that. Or it is only like that in the most unspecific sense—it is only like that insofar as it is a plea for all of us, black, white and everything in between, to rebel against these antiquated, prefabricated categories thrust upon us and to develop both more specific and more generalized ways of understanding ourselves and each other.

Put simply, I am arguing, on the one hand, that it would benefit us all to do away with abstract color categories such as “black” or “white,” and enormous geographic designations such as “Asian,” and impossibly expansive linguistic designations such as “Hispanic,” and almost meaningless turns of phrase such as “people of color,” and narrow ourselves down further. We should all aspire to be as exquisitely specific as you have been describing yourself as a descendant of “Zoroastrians who landed on the Gujarat coast from Persia and petitioned an Indian king for asylum in the eighth century.” On the other hand, I am hoping to persuade anyone who will listen to be even more sweeping in their understanding of themselves and each other: as one member among billions of the human race, each and every one of whom does not have to stretch back very far in order to find a common ancestor.

You ask if I’ve had chance to develop any further ambivalences and fears about the identity my daughter might assume in this divided world that would attempt to seal her into boxes. I don’t, not now, not any longer. And quite possibly, not yet. The fear might return. I can’t address myself with certainty to the future. But your other question, I do know how to answer. What my daughter—and my son now, too—owes her ancestors is simply to know herself fully. If she does that, she will know them, too, and she will know what they endured, and she will know the lies that justified their mistreatment. And, finally, she will know that her very existence disproves the logic of any so called divisions.

And you—do you feel your “race” has lost meaning and coherence in Argentina, in a society that never expected you to be there in the first place? In other words, in a society that never developed a set of behaviors to exclude you? Personally, this ability not to fit in has been one of the most profound benefits of living outside of the society I was born into. I wonder if you would have thought about these issues the way you have come to had you never gone elsewhere?

In kinship,

Thomas

Buenos Aires, 29 October 2019

Dear Thomas,

I am disheartened to hear that some critics regard your book as “an attack on blackness.” I had precisely the opposite impression.

Your maternal great-grandfather, Anton Spath, you tell us in the book, was a German basket-weaver, who immigrated to Baltimore in 1835. You describe this European ancestor with respect and affection. And then you add this devastating comparison:

I cannot help but know that at the same time Anton Spath was amassing his property and enjoying, as a total foreigner, all the power, dignity, and security that come with that ownership, my father’s people—many of whom had been in America for many generations before Spath was born and could trace their ancestry to both Europe and Africa—were enslaved not so many miles away.

I read this in tears—and the screen is a watery blur at this moment, as I revisit it. You provide no names, no descriptions and yet I have a sense of them: their human dignity and their suffering. As I understood it—correct me if I am wrong—it's partly loyalty to them that made you reluctant to abandon the idea of yourself and of your children as black for so long.

I don't believe there is a supernatural afterlife: we must be each other's afterlife. We keep the dead alive in conscious memory. But we also carry their legacies with us even when we know or remember nothing about them as individuals. Irvin Yalom calls this phenomenon rippling. Each person impacts those around her, inspires relatives and friends—and they in turn pass those influences on to others, in ever widening circles. These emotional, intellectual legacies that spread through personal acquaintance or through reading may be more important than the genetic ones. George Eliot has probably had more of an impact on my life than a Parsi great aunt I never knew.

In your letter, you highlight how unhelpful the mid-range focus is. We need to get away from imprecise notions of groups like Asians, Hispanics, whites and blacks and either, you write, “narrow ourselves down further,” down to our specific individual lineages or “be even more sweeping” in our understanding of ourselves as members of the human race, all interconnected.

And your reminder that we do “not have to stretch back very far in order to find a common ancestor”—evokes an even wider fellowship than that. In The Ancestor's Tale, Richard Dawkins uses the allegory of a pilgrimage back through time to chart the evolutionary history of our species. At each waystation, we meet a common ancestor and Dawkins muses on what we have in common. As we travel further back, the concestors, as he calls them, superficially resemble us less and less closely—but what we share reveals ever more profound insights into the nature of life on this planet. We often try to identify our tribes by salient visual characteristics, by brown skin or epicanthic eye folds: but to really understand human nature, we must, like Dawkins’ imaginary pilgrims, reach far deeper into the past and find the more profound points of commonalities.

You ask if my “race” has lost meaning and coherence in Argentina. Actually, I've always had trouble answering the question where are you from? In a literal sense, I am from a Karachi bedroom, where, one dusty autumn, behind slatted wooden blinds, beneath a tented mosquito net, an ageing Parsi bachelor’s plucky little sperm gently pierced one of my Scottish mother’s last viable eggs and, over a mild subtropical winter and spring her belly swelled beneath the psychedelic swirly paisley dresses of the late 60s.

But I left Pakistan at age eight and have never returned. The Parsi community there has almost completely dissolved—it’s become dangerous to be a non-Muslim in the so-called land of the pure. I don't feel I’m from Scotland either—I’ve never lived there for longer than a year consecutively. I grew up mostly at an austere, old-fashioned boarding school in the town destroyed by bulldozing aliens at the beginning of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy and then, more happily, during a decade at Cambridge University. I don’t feel I have a hometown.

I’ve always thought of my rootlessness, my half-caste mongrel background as a lack. It’s only recently that I've come to realise that it might be a strength.

As you say in the book, the idea of mixed race is a fiction because it implies that others are pure, unadulterated, straight up, neat. Whereas we are all the products of promiscuous mixings and blendings, shufflings and minglings, both shaken and stirred. And most of us are exiles from our ancestral homeland. We’re all foreigners in a sense, almost everywhere. But those of us who are more obviously, superficially foreign, more clearly the products of unions between people from different “ethnicities,” our parents pioneers of intermarriage, perhaps we have a especially clear opportunity to challenge perceptions of race.

“This ability not to fit in has been one of the most profound benefits of living outside of the society I was born into,” you write. I am very intrigued by this counterintuitive claim—and it makes me, the deracinated, indefinable, foreign-accented mutt, very happy. I want to know more about how that has influenced your writing, your relationships, your politics, your understanding of yourself as a father—or whatever else you feel you want to highlight.

Meanwhile, I send my warmest love from a southern spring,

Iona xoxoxo

Paris, November 4, 2019

Dear Iona,

Thank you for your rich and thought-provoking response to my previous note. I have been traveling and am only now back in Paris, back dropping my children off at school and daycare and back taking my place at the bustling counter of the little Turkish restaurant around the corner from my apartment. I like blending into the background here. It feels rejuvenating to lose myself in the melodic cacophony of languages I can ignore, to allow myself to become inscrutable again in a society that doesn’t really think about me at all.

The criticism from some readers has taken a familiar shape but manages to surprise me every time. I can’t get used to it because it feels as if it is directed at a target other than the text I have published. This morning I woke up to a series of texts from a slightly older “black” friend (I use quotes here simply because I wish to signal my unwillingness to accept the factuality of the term, but I should clarify: he is of Haitian-American descendant, not a descendant of Southern slaves).

My friend observed, not without an evident affection and love that is peppered throughout a years-long exchange, “You don’t reject race. You embrace whiteness. You reject your black heritage very thoroughly. And you go all into your white half (along with your marital whiteness) in all their glory and nuance.”

My response was that such a take was genuinely baffling to me. It was on purpose—not at all by accident—that the book opened with twin epigraphs from two of the most important writers in my life, men I would count as literary fathers of mine:

It was necessary to hold on to the things that mattered. The dead man mattered, the new life mattered; blackness and whiteness did not matter; to believe that they did was to acquiesce in one’s own destruction.

—James Baldwin, Notes of a Native Son

Why waste time creating a conscience for something that doesn’t exist? For, you see, blood and skin do not think!

—Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man

When writing, I had made the conscious decision to ground all that would follow in these “black” American perspectives because they are fundamentally dear to me, and also compelling. I chose them as members of the intellectual community that I would like to inherit. Beyond that, throughout the text, I express devotion to and admiration for my father, whose love and sacrifice shaped me—and yes, as you note, it was and is a sense loyalty to him that had for the longest time made it feel impossible for me to turn my back on a sense of racial essentialism even after that idea had revealed itself to be absurd. And finally, the transformative and inspirational encounter in the book is with the “black” American conceptual artist and philosopher Adrian piper, while the life-altering reading experiences that give the project some necessary affirmation come from Barbara and Karen Fields’s Racecraft and Paul Gilroy’s Against Race—all of these writers are “black.”

By my friend’s measure, why does none of this count? His response was unsatisfying. Something about these self-appointed intellectual inspirations of mine—the Pipers and Ellisons and Baldwins and Fieldses not being blood—something about my father not being enough. Something about not being able—or supposed—to choose the tradition and members of a community you want to be aligned with.

It seems to me that some people just don’t want to have as wildly specific a conception of themselves as your own beautiful understanding of your own conception in a Karachi bedroom buzzing with mosquitos. They prefer the mid-range, as you put it. We certainly can’t make them want to zoom in—or out. But what is frustrating to me is the reluctance to engage with the argument on its own terms—as a rejection of race tout court, not a rejection of blackness or a denial of anti-black racism that unfortunately persists.

Another (apparently “mixed-black”) man on Twitter recently wrote: “I finally figured it out: what Thomas is actually after is a kind of hyper individuality most people would recoil from. He uses language about race but that is a mid-direct. Isolated. Untethered. Only I. Never we. Sounds dreadful.” [sic]

I don’t know who this man is, but I responded to him because the presumption bothered me. I don't live an isolated life at all, but I do choose the heterogeneous assortment of people I'm connected to rather than content myself (as I had before) with a readymade sense of myself handed down from a racist and oppressive past. Why would friendship, kinship and community that you will into existence be perceived as inferior to that which to you belong to through nothing more than accident of birth?

What I haven’t encountered yet—but would be interested to see—is a full-throated, non-racist counter-argument for race as a societal good. I may not have to wait much longer. I'm afraid that this is where certain segments of the left may well be headed.

With envy of your southern sun from a wet and gloomy Paris!

Thomas

Buenos Aires, 5 November 2019

Dear Thomas,

I share your bewilderment at this interpretation of your book: “You don’t reject race. You embrace whiteness.” There's a clear implicit criticism here that I'd like to try to unpack. First, a counterexample might be helpful.

Last year, I interviewed John R. Wood jr.—and was startled to hear him say he even had some sympathy with white nationalists. The son of a “white” father—though, as the founder of Dot Records, many of his dad’s icons were black musicians—and a “black” mother, he feels “as white as I am black” and called upon to “equally honour” both sides of his heritage (hence his empathy with some manifestations of white pride). Because of his appearance, he sometimes feels a need to remind others of his whiteness—which would otherwise be invisible. “I’m African-American, but I’m also European-American and that’s what surprises people,” he told me. John’s work is about building bridges—between Democrats and Republicans, especially—so it’s unsurprising that he sees himself as a racial bridge between two discrete communities. This is an embrace of whiteness (and blackness)—and it is instructively different from your approach.

One thing you share struck me though: like you and your brother, when John was alone with his white parent, lots of concerned people wondered where his mum and dad were. It’s understandable that many of us who more closely resemble one parent are keen to stress our shared heritage with the other. In a sense, if your daughter were to describe herself as white, it would be a denial of her connection to you. But, equally, if you were to call yourself black, it would be a denial of your own mother. Isn’t it perverse that, in encouraging people to paste coarse-grained racial labels onto themselves, we can end up obscuring or devaluing their most intimate blood relationships of all?

This is a practice with an ugly history. During the British hegemony in India, many extramarital and illegitimate mixed race children were born. Those who looked white were often quietly passed off as the offspring of British marriages or sent back to Britain to be raised by aunts, etc. Those who looked Indian were left behind, sometimes sent away to orphanages as an embarrassment. Siblings were even separated at times: demonstrating as clearly as we could possibly wish just how superficial our categorisation by skin colour really is. Skin colour inheritance is non-Mendelian and the appearance of “mixed race” children is unpredictable.

My life might have been different if I had inherited my father's milky coffee complexion. Perhaps I would have been derided as a Paki in the Britain of the 80s; probably, though, more fully accepted by the ultra-traditional elements of the Parsi community (who still deplore the idea of marrying out). But the important thing is: this is a question of the accidental inheritance of a few alleles. I would still have been fully and completely the same me.

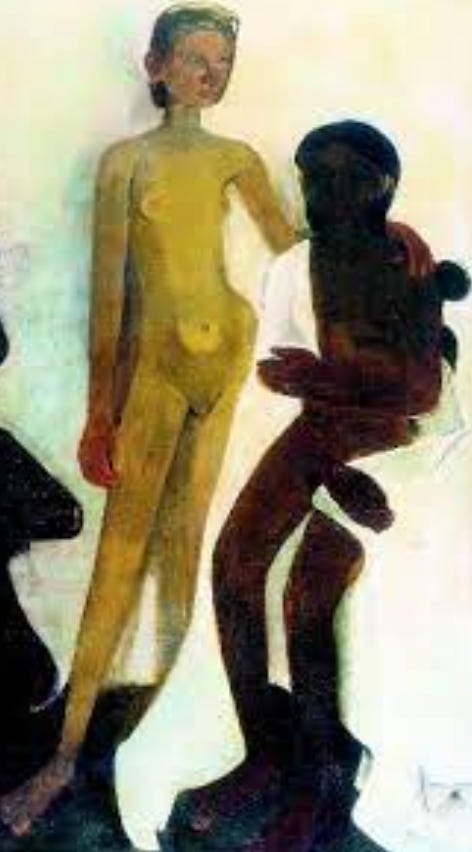

There's a famous 1939 painting by Amrita Sher-Gil, the daughter of a Sikh aristocrat father and a Hungarian Jewish mother, called “Two Girls,” which I viewed in the Jehangir Art Gallery while I was living in Bombay.

It’s not usually interpreted this way, but I see it as a split self-portrait, akin to Frida Kahlo's of the same year, “The Two Fridas” [the header image for this post]. Sher-Gil, to me, is here literally embracing her Indian side, with palpable tenderness and protectiveness. I also associate the picture—more idiosyncratically—with the Star Trek Voyager episode “Faces,” in which the mixed-species officer B’Elanna Torres is separated into two women: one Klingon, one human. But—unlike B’Elanna—we are not composed of halves that evolved on different planets. We’re all—“mixed race” or not—completely human. I don't believe there is some Indian Parsi essence, some typically bawa personality melded with a typically Scottish one inside me. We’re all a mixture of our fathers and our mothers; we all have twinned chromosomes, we’re all two people stitched together into one, in that mysterious weaving in the womb.

So, why the fear that you are somehow betraying a cause, shirking your duty to identify as black? Well, politically, there's strength in numbers, so activists want to be able to count you as on their team—when really, I believe, they should widen the circle and bring everyone on board with their aims. And, culturally, people want to claim the eminent members of their community, to feel pride in themselves by proxy, to say: look, we produced this person, as if parenthood were somehow collective, like a kind of racial kibbutz. But you're an artist. And the artist—however rooted in and inspired by his community he might be—even if that artist is a writer as wedded to the idea of his race as Ta-Nehisi Coates, who frames his own most well known book as a letter to his black son—always addresses the wider concerns of humanity. When a writer moves us, it's because he transcends the narrow boundaries of his original group, to speak to everyone.

You talk about “the kinship and community you will into existence” in friends and associates—in a wider sense, as a writer, that community is potentially everyone. I think your "black" readers fear that, amid that ocean, their specific history will be washed away and their specific needs ignored and forgotten. How can you—can we—best assuage those fears and still stay true to this belief: homo sum humani nihil me alienum puto? Everything important is shared among all of us.

We are all, after all, far more closely related than we usually choose to believe.

In kinship across an ocean,

Iona xoxo

Dear Iona,

Greetings from cold, rainy Paris. It’s been a hectic two weeks since we last corresponded, so please forgive me the delay. I’ve made the transatlantic commute twice this month with a trip to Dallas thrown in for good measure. But I'm grateful for your letter. I think you get to the heart of the issue I'm confronting when you say: “There’s strength in numbers, so activists want to be able to count you as on their team—when really, I believe, they should widen the circle and bring everyone on board with their aims.”

Before the book was published, we excerpted it in the New York Times Magazine. The comments for that piece were overwhelmingly positive, and when they were critical, they were nuanced and respectful. A lot of commenters brought their personal experiences to bear on the conversation. One commenter revealed an uncommon honesty when he wrote, in effect, “Look, I get the arguments, and they may even be correct, but at the end of the day, I’ve got a limited amount of time and energy and I just want to know where you stand. Which side are you on?” I was struck by the real emotion and vulnerability such a statement (which I'm paraphrasing here) conveyed. And of course I’m sensitive to it. But, for me at least, that's not the extent of what writing—which I think must always be the pursuit of the truth, wherever that may lead us—can ever be allowed to become. There’s a space for activism and advocacy, to be sure. But writing must be something else or we are in deep trouble indeed.

What you say about John Wood is interesting. I understand his position, but it’s quite different than my own. I would never be able to say I feel myself to be as white as I am black—or vice versa. I don’t know what feeling “white” or “black” really means anymore—and if I’m honest I never did. Some of the things I’ve known and still know: I love my mother; I love my father; I love the sounds of John Coltrane, 2Pac, Jay Z; the images and ideas of Dostoyevsky, Hemingway, Proust; the food and wine of France, of Texas; the silhouette of Michael Jordan slicing through the air ... What I’m trying to say is that “white” and “black” fail me, and in retrospect they always have. I've always taken my cues from all directions—my loyalties and affections have always been varied. Where I think John is saying he’s this but he’s also that, I’m simply insisting that I’m neither.

I don’t know if such a way of interacting with the world could ever satisfy someone seeking, at the end of the day, just to know where you stand. But the more I go out and speak about the book, and the more people I meet and listen to, the more I'm convinced that many, many people are not satisfied with the limitations of the sides we've been forced to take.

For now this is where I am. I don't know where else to go, or what else can be said. It seems like we’ve arrived at something akin to Kierkegaard’s “leap of faith.” You either make the jump and believe that things can and must be otherwise—that we can will ourselves into a better, less restrictive world. Or you refuse to make such a move. What do you think?

With a strong embrace,

T

Sincere thanks for passing along this heartfelt exchange. I’ve had an eye on Mr Williams for a while and will be getting that book of his. A few months after this correspondence, as the racial drop zone reeled in response to the Floyd killing amidst covid disruption, he posted a reading list that included some of the works he had alluded to in your letters. I’m a bit slow on the uptake, so am still working on it.

The issues are personal for this aging white guy. At 14, 3 years after my mother passed at home in the small midwestern town where I’d done most of my growing-up, I took my place in a new household with my dad’s new partner and her three daughters. Ethel was a light-skinned black woman while Mikki, Claudia and Renita were all darker. The arrangement was awkwardly possible in our new town, a near suburb of LA, because it was undergoing a rapid demographic transformation. It lasted almost three years, ultimately collapsing under the burden of, among other factors, a 30+ year age gap between the two adults in the equation.

The old man and I stayed in the house and I graduated from the high school down the street on schedule, but well in advance of the still below-the-radar movement toward a level of racial mixing that is now visible and widely accepted. As a nearly clueless young swain I was prone to many missteps, but the conviction that my black and brown friends, classmates and teammates were irreplaceable had become permanently rooted. I was able to parlay that into a secondary school teaching career across the tracks from my adopted town (ironically self-appointed “The All-American City” in the years before it underwent the change) because, despite my paleface, my comfort level was sufficient to the task of commuting to ‘South Central’ for (most of) the last 30 years. I’m happy to have had the opportunity, comfortable in the role of aging white boy.

And the ties that bound the patched-together step-family have been renewed on a friendly and positive footing. We’ll be having a wee bit of a get together in about a month. The strife of history demands some accounting of course, but that is played-out on a different stage. The more intimate level of connection is what we carry around in our heart of hearts, and it can’t be effaced. We’re slowly arriving at the place it can call home. Let more keep coming.

Loved these letter then and Iove them now! I credit you, Kmele, and Thomas with realizing that race is a negotiation between the individual and their neighbors.