Tinder and the Illusion of Control

As some of you might know, I recently ended a two-year relationship (which actually began through Twitter—I write about this here) and returned to the dating apps, of which I am a veteran, to look around for a potential new boyfriend.

This introduction might seem to promise an amusing catalogue of terrible dates, a bestiary of bizarre men—but if you are hoping for that, you are in the wrong place. I decided to date anyone I matched with who showed serious potential one at a time and, after only a few days on Tinder, found someone intriguing enough that I am focusing on him alone for at least a while. (UPDATE: sadly, that little minnow of possibility has since been tossed back into the ocean and I am fishing once again.)

But, even in the short time that I have been on the app, I noted a few deeply unsettling things about Tinder—and, in my experience, the other apps (Bumble, Hinge, OK Cupid, eHarmony, etc.) all share the characteristics that trouble me: in this respect, Tinder is perfectly representative of them all.

You see, in real life, I have never been presented with a selection of possible dates, a virtual menu of men. Offline, things have almost always developed in this order: I encounter someone, am charmed, enthralled, bewitched, enamoured and then finally, with trembling uncertainty, find myself with him in a situation that I hope is romantic (I’ve rarely been sure), anxiously and obsessively interpreting every look and word, waiting to see if the attraction is mutual, if my longing for physical and emotional intimacy will be reciprocated.

Tinder, by contrast, presents us with what a chess player might call a move order problem: in real life, we feel a spark of attraction for someone and then we date; the app encourages the reverse—first, we date, then we hope the attraction will manifest itself. We hope that we can summon the spirits of the isle; that we can take this heap of dry kindling and spark a flame.

Swiping through the endless gallery of photos and bios, searching for anyone who stands out, I feel as though I am narrowing down a list of job candidates. People often complain that the apps promote deceit, ghosting and other behaviours indicative of a lack of regard for the people you’re interacting with and they do so for the same reason that makes it hard to find a serious relationship on there—because the user feels that he or she has so many other options and comparison is the thief of joy.

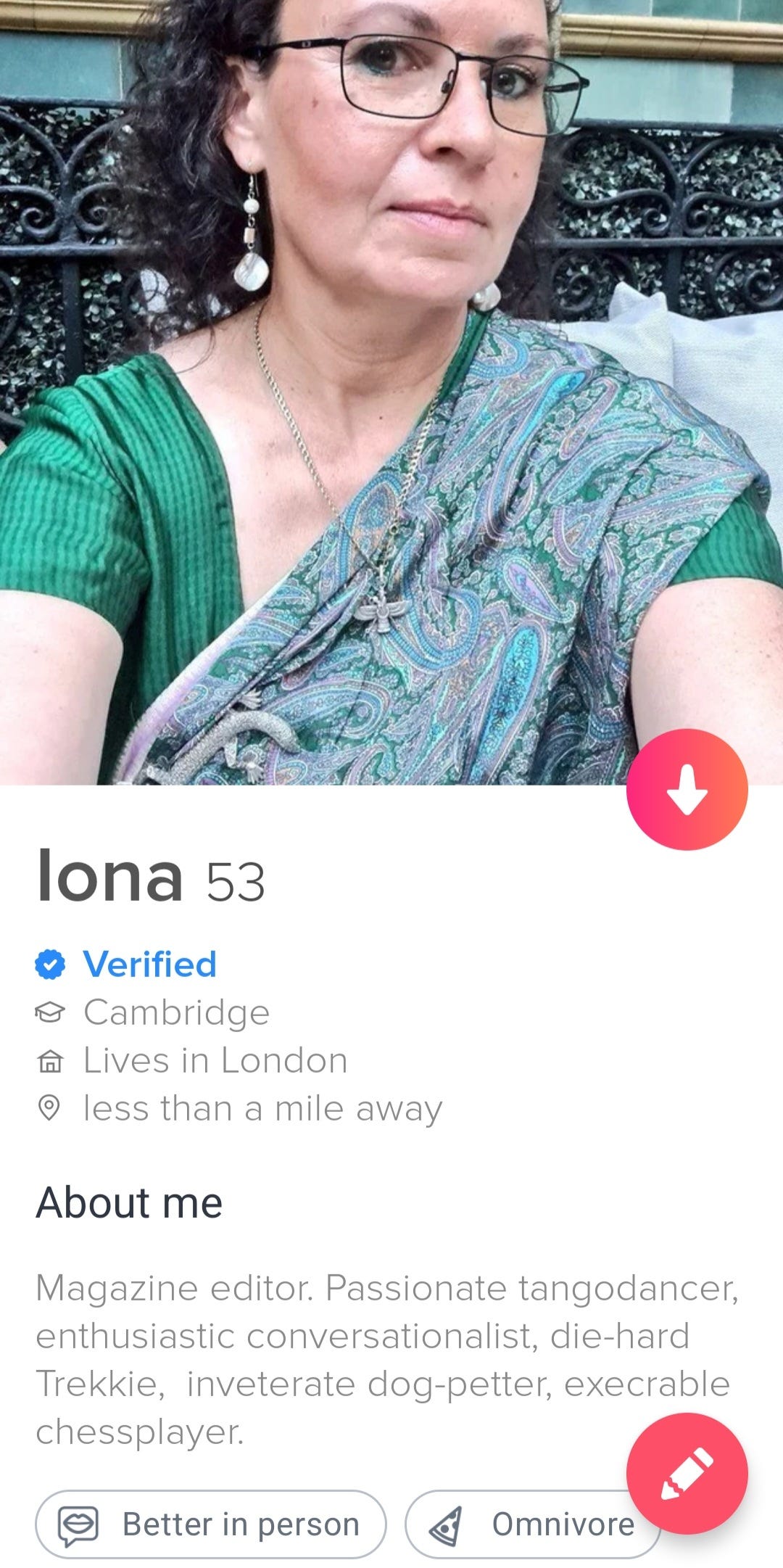

But I do not feel inundated by meaningful options on dating apps. Reducing people to a postage-stamp-sized photo and a few lines of text tends to smooth out their differences, conceal their idiosyncrasies, make them seem interchangeable. Most people are not expert writers and it is especially hard to write about yourself without seeming conceited or to write about what you hope to find in a partner without appearing entitled.

As I read the same descriptions again and again, beneath photos of hundreds of very similar looking men, it doesn’t feel like real choice; it feels like standing in front of a supermarket shelf of almost identical products, differentiated only by minor variations in packaging, in paralysed apathy and dismay. I have the same sinking feeling as I do when I peruse the endless menu of an especially bad Indian restaurant and see a hundred dishes with inviting names, which I know from experience will all turn out to be chunks of meat and vegetables rendered indistinguishable by being blanketed in the same two sugary red and beige slops.

Dating apps are often cited as an example of hypermodernity—our technology places us in a situation that had no equivalent in the ancestral environment, creating a disorienting mismatch between our evolved intuitions and the circumstances of modern life. But, to me, the use of apps feels more like a regression to an age before romantic love was the paramount model of relationships in the west: to a society of matchmakers and arranged marriages, when prospective mates were evaluated on the basis of a laundry list of qualifications, when aunties scrutinised heights, salaries, qualifications and star signs and put together lists of the most suitable candidates, to be inspected on formal visits. Now there are no go-betweens: we are our own matchmakers. We are placed in the awkward position of having to advertise our own virtues and don’t have the benefit of community gossip to guide us in our choice of suitors.

The problem is that you cannot shop for love in the same way as you can for an eyeliner. Love can grow unexpectedly from unpromising beginnings—but it cannot be forced. You can nurture a relationship you already have, deepen an attraction you already feel, but you cannot manufacture desire or romantic love for someone, no matter how many searching questions you ask.

I have drunk Malbec deep into the night until my teeth were purple and my stomach churning, sobbing out the snotty pathetic tears of self-pity when in the throes of an unrequited crush. But I have also, more than once, rejected the sincere love of a kind man who could have provided a comfortable life and pleasant companionship because I just did not, could not find him sexually attractive—and that was far more heartbreaking. Erotic attraction is unpredictable and, far from being superficial, my involuntary responses to people’s looks and manner, responses that produce desire or absence of desire for them, lie in the deepest stratum of my being, bone-deep—a long way below the level of conscious control. I have no influence over them.

Yet, against all the odds, people do fall in love with their Tinder dates. Almost everyone I know who has started a serious relationship in middle age has begun that relationship online. This is surely partly a dispiriting symptom of the increasing proportion of interactions that take place online, rather than in the flesh. But the proliferation of apps has also brought new possibilities and hopes. It’s never been easy to find love as a postmenopausal woman. Even when I am socialising furiously, in real life, the number of men I meet within my age group who are even straight and single—setting all other considerations aside—is tiny, while online I can view twenty in a minute. It’s a start.

I have little nostalgia for the more sedate courtship rituals of the past. In an earlier age, surely I would by now have resigned myself to a life of gossip and knitting, of babysitting grandnieces and nephews and attempting to take a vicarious pleasure in the happy romances of comic novels and in discussing the details of other people’s weddings. Now, at least, I can still be a contender. Wish me luck.

I began blogging back in the early days of 2002. I found that sharing the personal views of people enabled me and them, over say a year or so, to gain a deep insight into whom this person was. When we met in the flesh later, the good feelings were confirmed. High trust in most situations and affection in most. This is for both men and women. Your twitter feed is very much like how we used to blog then and I hope for you the same result. Wishing you luck, Rob

I love this writing! So clear-eyed and free of self-pity. There’s much that suboptimal about tinder and modern love, but also a lot that’s curious and bears investigation. I’m sure I’ll be a fan of your substack!