The Map Is Not the Territory

Looking for love in Australia’s capital

It’s my first coach journey in Australia and it’s reminding me, oddly, of a trip I used to take regularly in what seems like another life—from Bombay to Pune. Like that journey, it’s three and a half hours of gentle ascent through wooded countryside that will transport me from the Big Smoke to a calmer, smaller city. As we leave the Sydney suburbs behind and lumber quietly upwards, as if riding on the back of a placid elephant, it's hard to imagine that there will be a city of any kind at my destination—let alone a capital city. To either side of me and ahead, there is only scrubby grey-green eucalyptus forests and then, as we round a bend, a huge expanse of brackish water, a giant hillside lake patrolled by pelicans in their chic monochrome black-and-white uniforms. The straggly grass at the ragged shoreline is dotted with small, brown birds, unidentifiable from the bus but perhaps pipits (Anthus australis). Ibises—our much maligned bin chickens—soar high, high above. I am reminded of the heights of Papallacta in Ecuador, of the lochs of the Scottish Highlands. But it's hard to tell the highlands of Latin America and those of Europe apart. Intersperse photos of Tierra del Fuego with those the Scottish Hebrides more than eight thousand miles away and you'll have difficulty saying which is which. Here, the grey green foliage and the peeling barks of a million eucalypts mark this instantly as comfortingly Australian.

A friend described Canberra as a “moon base.” And that seems apt: it’s the kind of city the writers of a late 80s or early 90s sci fi series might design on another planet: all straight lines and long vistas, with its huge slabs of brutalist concrete facades and the oddly triffid-like structure of the new parliament perched legs akimbo on a small hill. Against the grand scale of the buildings—each one proudly proclaiming that it is the national this or the national that (“Everything’s national here,” my host jokes, “the national fart, the national pee.”)—the plazas, the long sightlines across the city from the war memorial to Parliament House, there are relatively few people on this bank holiday long weekend. And all around the mountains encase us, tempting, beckoning. This enhances my feeling of being on the set of a sci fi show, immersed in retro-futurism, with not quite enough extras to render the make-believe metropolis convincing. I am charmed by this—how could I not be? Endless watchings and rewatchings of Babylon 5, Stargate SG1, Deep Space 9, and Farscape have prepared me to feel at home on an alien world.

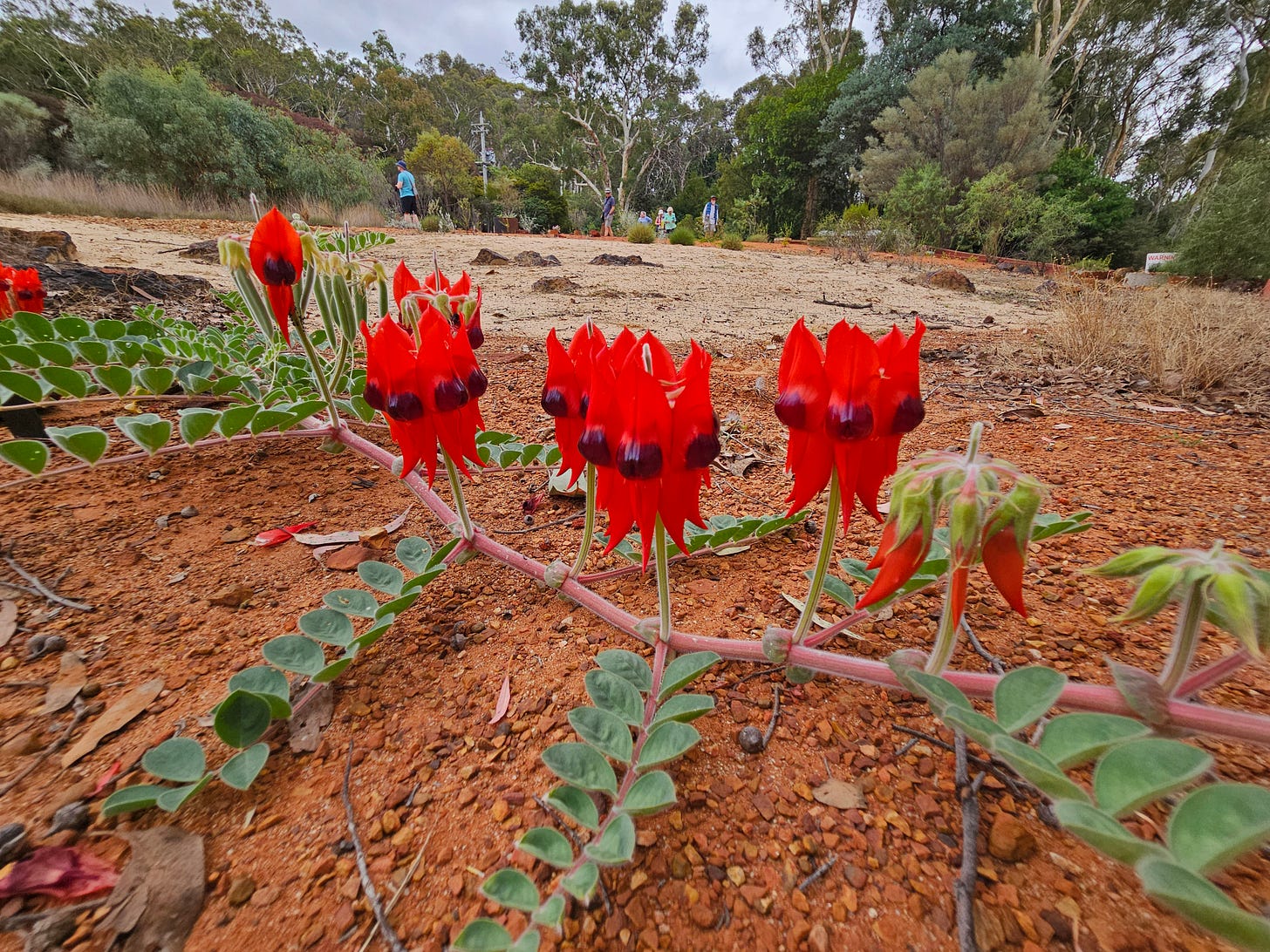

There’s a bright unreality to Canberra that it shares with other artificial capitals: places that did not accrue that status organically, by attracting the largest share of the population, but were appointed by committee, as a compromise between competing factions. I feel it as we stand at the top of Mount Ainslie, looking out at the city spread before us, each building carefully aligned with the watercolour sketch Marion Mahoney Griffin made in far-off Chicago, before she ever set foot in Australia. I feel it in the botanical garden—perhaps my favourite of any Australian botanical garden so far for its sub-alpine feel—when I come across a basin of rusty dried-blood-coloured soil, festooned in places with the freshly-shed-blood red of Sturt’s desert pea. The blooms sit bolt upright, in circles, like party hats, each with a round blackish grape ‘boss’ in its centre, like a cyclopian eye. This is a miniature version of Australia's central desert: an oasis in reverse amid the four-season climate of Canberra, wildness tamed into an exhibit. Bearded dragons pose on rocks; lizards flick their grape-popsicle-stained tongues. The botanical garden, like the one in Brisbane, ends in a trail that leads you steeply up a hillside to a summit. But unlike in Brisbane, here the dense eucalypt woods block the view so you can catch only glimpses of the city. All I could see was a plaque welcoming you to Ngunnawal Country and an old-style telecommunications tower (which was closed).

A few roads further, we round a corner in my host’s grubby but trusty old Volvo and find we are at a viewpoint designed to offer a view of Governor General’s house. At the end of a long, long expanse of lawn, a cream-coloured European-style house, different from others only in its size, stands out against a mountain backdrop. A mob of kangaroos bound across the grass, in perfect profile. At night, we attend a festival called Enlighten—the Canberra equivalent of Sydney’s Vivid—featuring light projections. Canberra is far more suited to this than Sydney: Sydney’s festival is a thirteen kilometre hike with the odd light show thrown in. Canberra’s concrete buildings, by contrast, form the perfect backdrop, the best possible blank canvas for the dragons and Japanese boats and blossoms and moonscapes projected onto them.

And projections feel apt for other reasons too: despite the architectural heft of its buildings, Canberra feels provisional, as though it had been lightly placed on the landscape, balanced on top, rather than rooted within. Australia often gives me this sensation: that a thin patina of modern buildings are perched atop hunter-gatherer territory going back tens of thousands of years. The deep past is more accessible here than it is in Europe or Asia, not buried beneath the accretions left by millennia of different civilisations succeeding each other. Australia is a blackboard imperfectly wiped. I can still make out the faint traces of what was written in a previous class—a class that lasted an aeon.