The Make-Believe of a Beginning

Navroze Mubarak!

Once upon a time, in ancient Persia, so the legend goes, King Jamshed ruled over a vast empire, stretching from the frozen wastes of Siberia to the scorching sands of Egypt. From Babylon to Rhodes, from Persepolis to Thebes, Zoroastrianism was the religion of the peoples living around the huge crescent of lands in which wild grains grew and hunter-gatherer nomads were turning into pastoralists and clustering into the first settled human habitations, the first towns and cities, the beginnings of civilisation.

Jamshed was so close to the Zoroastrian god that he had not a vizier or a first minister but an actual angel as his counsellor of state. That angel warned him of a catastrophic flood that would sweep the globe and, in preparation, instead of building an ark, the Noah of our story brought one male and one female of every species up to higher ground, to wait until the waters receded, which they did—pleasingly, fittingly—on the first day of spring in the northern hemisphere, the only part of the globe then known to man. That first day, as the people and animals scrambled and slid down the slopes onto the spongy, muddy flats that had so recently been ocean, they declared the beginning of a new time, a new day, Jamshedi Navroze, the day the Iranians still celebrate as their new year.

But people who are good at spinning yarns are not always good at maths. Perhaps it was just that not enough was known about the Earth’s exact speed and trajectory. How could it have been? These were a people who still believed in a geocentric universe in which the world was encased, like a Russian doll, inside sphere upon crystalline sphere. Or perhaps the makers of the calendar were simply seduced by the delights of symmetry. But either way, they divided their year into twelve months of thirty days each and the days of those months were not numbered but had thirty unique names, just as the days of the week do.* When they realised that this arrangement did not fit the reality of the changing seasons, they added five days to the twelfth month. This added up to a year of 365 days. You might think that that remaining quarter day, which completes the Earth’s orbital cycle of 365.25 days, would not be missed. But over time, of course, the calendar slipped ever further out of synch with the tilt of the Earth’s axis and the human New Year lagged ever further behind the natural one.

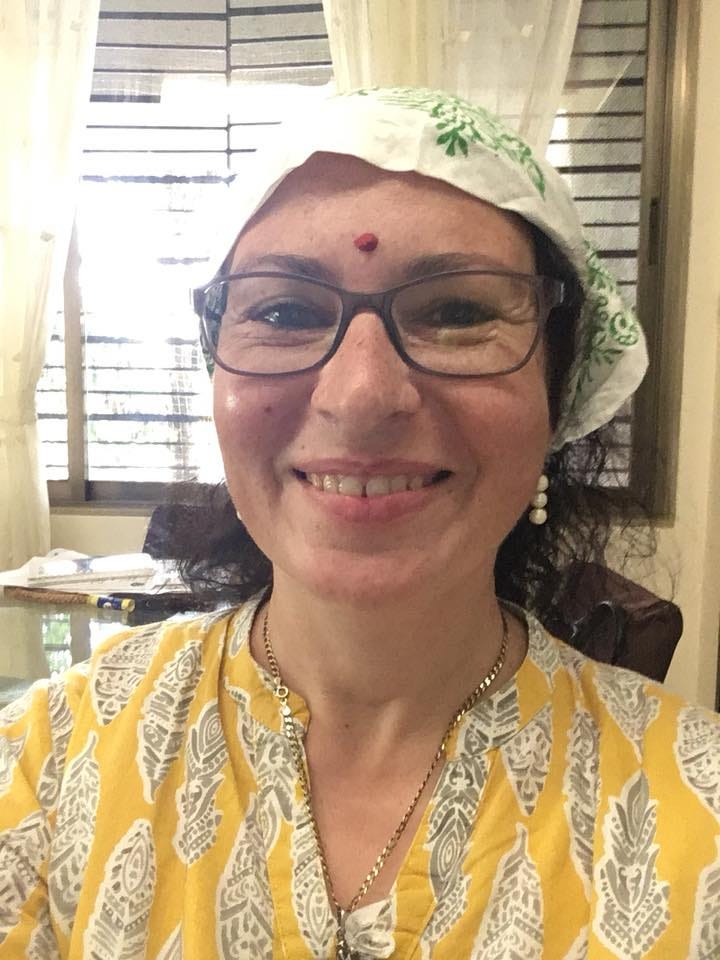

Many centuries later, when Persia was Islamised by the sword, a small group of Zoroastrians left for India. These exiles, like exiles everywhere, were highly conservative, nostalgic for the old traditions. They clung to the customary calendar until now we Parsis celebrate our New Year, the Shahenshahi Navroze, in August, a time that is not a beginning of anything, a time of harvest, of the hazy dog days of summer in the north and here in the south, winter’s crisp, bright, sunny last hurrah, its last chance to nip at my naked toes when I do my morning yoga on the balcony, the last outings of my woollen beanie, the last opportunities for Sydney’s ocean breezes to rouge my cheeks on the morning ferry. An August New Year is more fitting down here than it is in India, sweltering in the pre-monsoon heat. Spring is in the air here and new beginnings feel more meteorologically aligned.

But of course, every beginning imposed by human will is artificial. We choose a moment at random and we declare: here we plant our marker; here we place our starting blocks; here we draw our line in the sand. “Men can do nothing without the make-believe of a beginning,” writes George Eliot at the beginning of her novel Daniel Deronda:

Even science, the strict measurer, is obliged to start with a make-believe unit, and must fix on a point in the stars’ unceasing journey when his sidereal clock shall pretend that time is at Nought. His less accurate grandmother Poetry has always been understood to start in the middle; but on reflection it appears that her proceeding is not very different from his; since Science, too, reckons backward as well as forward, divides his unit into billions, and with his clock-finger at Nought really sets off in medias res. No retrospect will take us to the true beginning; and whether our prologue be in heaven or on earth, it is but a fraction of that all-presupposing fact with which our story sets out.

Since Eliot wrote those words in 1876, of course, science has established a beginning of cosmological time—the Big Bang, the moment when the stopwatch started and where there had been nothing, there was something: the New Year of the Universe. This cosmic beginning is unimaginable to me. To move from the macro to the micro, the beginning of my own existence—while imaginable—is hidden from my consciousness. Like the universe, when I began there was no I, just a plucky little spermatozoon delivering its precious cargo to a waiting egg, a puddlejumper docking onto a giant space station where the hatches opened and the crew strode out onto the promenade, ready to change everything forever.

Like many people, I cling to the illusion of the fresh beginning that a new year offers. I leap on every new year I can find—from the midnight chimes of 31 December to the lamps of Diwali and the red lanterns of the Year of the Snake. I’ve made many false starts in life; I’ve had several fresh beginnings. I’m on my seventh country, my fourth continent, in a place where in past centuries many people began their new lives, whether in sorrow—torn from everything and everyone they had ever known and loved, lurching across the wide ocean towards servitude in a land of unknown hardships—or in hope—with gold in their sights or sunshine or simply the excitement of the new. Here, amid alcoholics and petty thieves, many made that fresh state and prospered, just as my paternal ancestors the Parsis were to prosper in the new land they sailed to when they left their native Persia and crossed the Arabian Sea in wooden boats or made the arduous trek on horseback across the Hindu Kush.

Once again as the New Year begins, I hope this is the place in which I will flourish; I hope this is the year in which I will flourish. Our New Year falls in the middle of the calendar year, in the middle of the month, in the middle of the week. Every year, I find myself confused as to its exact date and have to Google it several times. The arbitrary nature of a New Year is therefore always crystal clear to me. As is the fact that this specific date will whoosh past like a Doppler shift, without altering anything. And yet, I feel optimistic. I’m alive; I’m healthy; I have my wits about me and I live in one of the most beautiful cities in the world. Life has many pleasures in store, both known and unknown. I have high hopes for the year, a vehicle straight from the showroom with that new car smell. My ride around the sun at over a hundred thousand kilometres an hour is here. I’m strapping in. Let’s drive!

*I’ve simplified this story quite a lot. You can find many more detailed version online: here, for instance.